Using a technique, they developed for studying eye fluid, Dr Mahajan and the team of researchers have found a way to measure ocular aging, opening avenues for treatment of numerous eye diseases.

Our Bureau

Stanford, CA

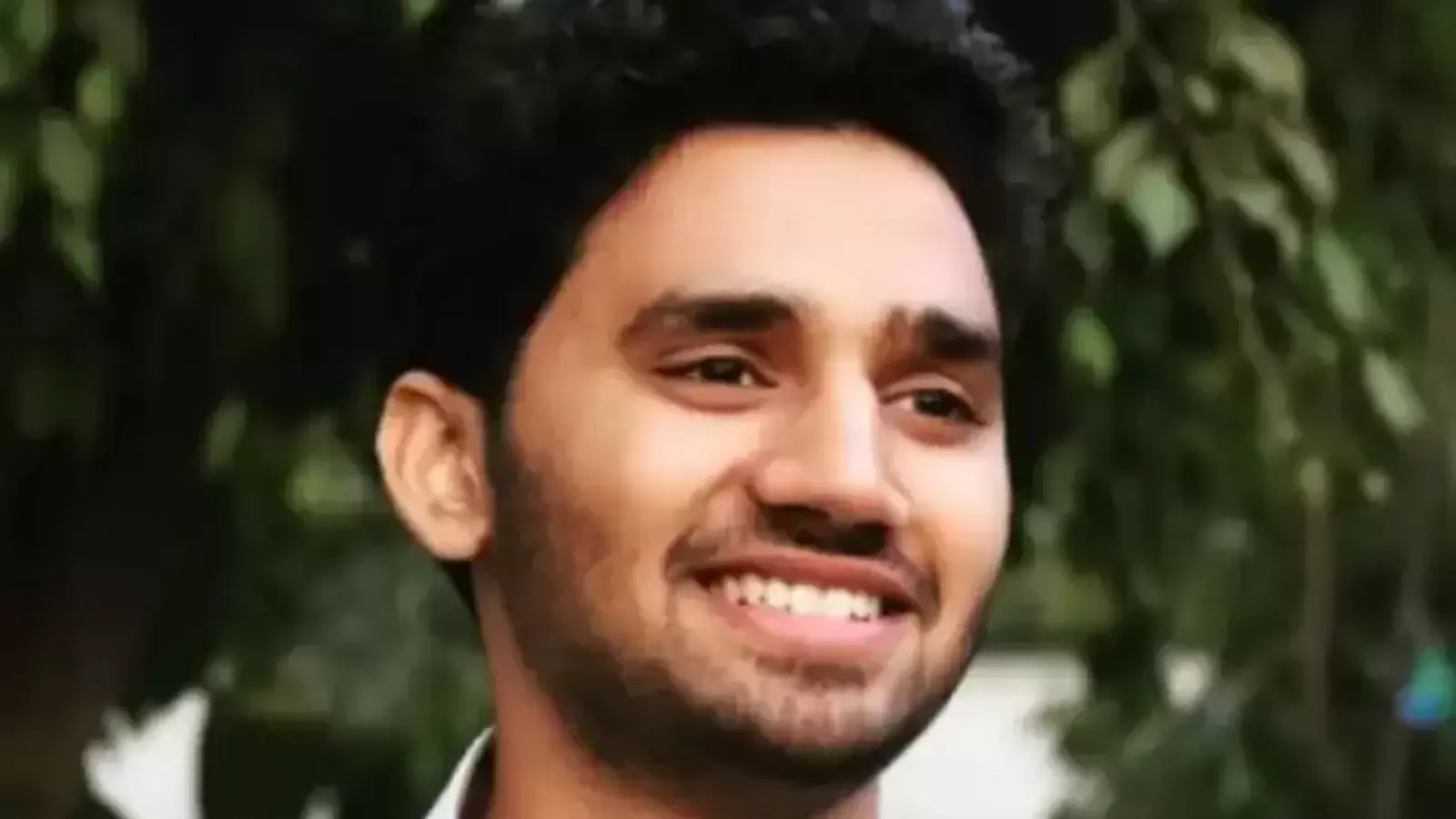

Prof Vinit Mahajan and a team of researchers, using artificial intelligence (AI), developed an eye-aging “clock,” indicating which proteins accelerate aging in each disease and revealing new potential targets for therapies. The scientists looked at nearly 6,000 proteins in the fluid and found that they can use 26 of them to predict aging.

Using a technique they developed for studying eye fluid, Stanford Medicine researchers and their collaborators have found a way to measure ocular aging, opening avenues for treatment of numerous eye diseases. The study was published by Dr Vinit Mahajan, MD, PhD, a professor of ophthalmology, who is the senior author, and Dr Julian Wolf, MD, a postdoctoral scholar in Mahajan’s lab, is the lead author of the paper.

Mahajan and his colleagues intend to apply the clock method to other bodily fluids to develop more effective drugs for a variety of diseases. “This is one of the best connections ever made that suggests disease triggers accelerated aging,” he said.

To glean the most information possible with small, renewable samples, Mahajan and his team developed a technique — TEMPO, or tracing expression of multiple protein origins. By tracing proteins to a type of cell where the RNA that creates the proteins resides, TEMPO allows the scientists to understand the cellular origin of disease-driving proteins with the hope that eventually they can target the cells with personalized medical treatments.

“The first step in developing any kind of successful therapy is understanding the molecules,” Mahajan said. “At the molecular level, patients present different manifestations even with the same disease. With a molecular fingerprint like we’ve developed, we could pick drugs that work for each patient.”

To better understand which cellular processes contribute to various eye diseases, the team analyzed liquid biopsies taken from the aqueous humor — fluid between the lens and the cornea — while patients were locally anesthetized during surgery. The fluid was collected in patients with three types of eye diseases: diabetic retinopathy, which causes blood vessels in the eye to leak, leading to vision loss; retinitis pigmentosa, which causes light-sensitive cells in the back of the eye to break down; and uveitis, inflammation inside the eye.

Dr Mahajan is a professor vitreoretinal surgeon and scientist in the Department of Ophthalmology at Stanford University. He earned his bachelor’s degree in molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley; and entered the Medical Scientist Training Program at the University of California, Irvine.