India’s chip ecosystem is undergoing its most significant transformation yet, moving from low-value assembly to deeper manufacturing, materials research and the long road to building indigenous semiconductor IP

Our Bureau

Mumbi

India’s semiconductor landscape is entering a decisive second phase as industry leaders and policymakers push the country beyond assembly-led growth toward high-value manufacturing, materials capability, and long-term chip design autonomy.

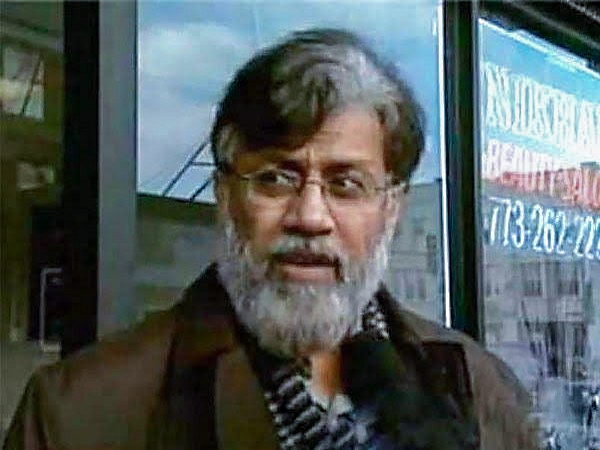

The shift, industry veterans say, is both structural and strategic. Vinod Sharma, Chairman of CII’s National Committee on Electronics Manufacturing and Managing Director of Deki Electronics, described India’s electronics journey as a “4 x 400 metre relay race,” with the country now firmly in its second leg. The first phase, he noted, was dominated by assembly expansion driven by the Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme. “The PLI for large-scale electronics did very well. We are now coming to a sunset of that PLI,” he told ANI.

What comes next is far more complex—and consequential. Backed by sustained policy support through initiatives such as the India Semiconductor Mission (ISM), the Electronic Component Manufacturing Scheme (ECMS), and a heightened geopolitical urgency to secure supply chains, India is now pushing into components and materials, areas where it has traditionally been dependent on imports.

Sharma said the ECMS has triggered unexpected investor enthusiasm. “The government has received under the scheme almost twice the amount of investments they were expecting,” he said, calling it a “very big compliment” to the policy as well as to global interest in India’s manufacturing rise. Approvals, too, are being cleared at an accelerated pace, with MeitY processing “eight to ten approvals every week.”

A key driver of this pivot is geopolitics. India, like several economies, is responding to China’s tightening control over critical materials and rare earth elements. “The Chinese policy of weaponizing key supply chain material has triggered us to now take steps which will make us an Atmanirbhar Bharat,” Sharma said. The government’s ₹7,600 crore rare-earth initiative is part of this push, though Sharma cautioned that capability-building in mining, refining and applications will take time. India, he added, is now exploring a wider range of metals essential for chips and electronic components.

But materials are only one layer of India’s semiconductor challenge. The other is intellectual property—long seen as the missing piece in India’s electronics ambitions.

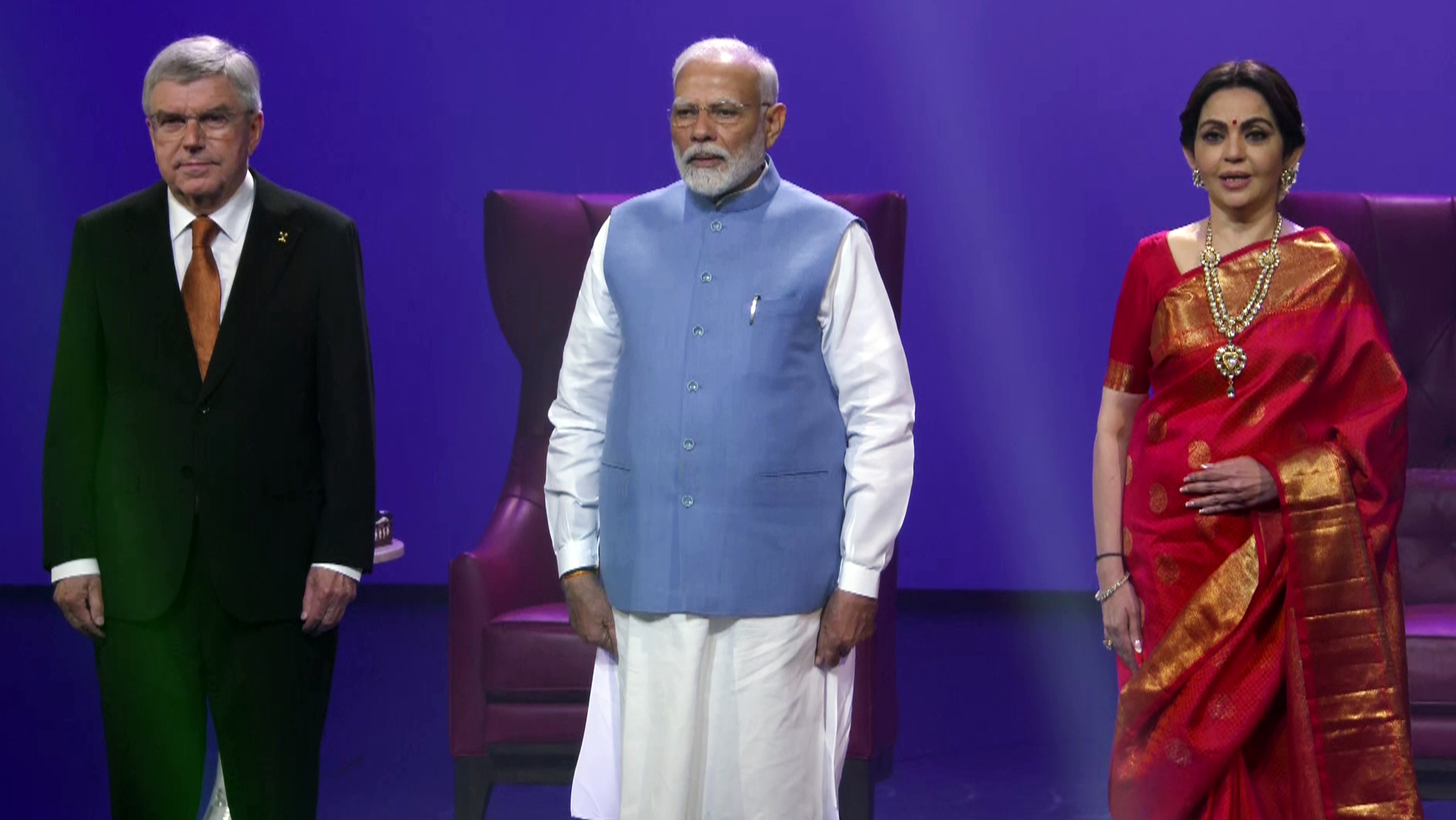

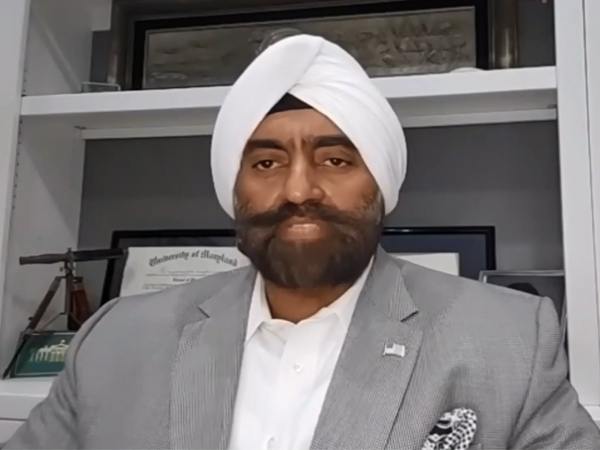

At the ‘From Chips to Circuits’ forum in New Delhi, industry leaders underscored an urgent need for collaboration and deep R&D to avoid repeating past failures. Jasbir Singh Gujral, Managing Director of Syrma SGS Technologies, warned that without unity in research, the sector risks stagnation. “If you don’t unite and R&D, we all will die in line with the old TV industry,” he said.

Gujral argued that India has long been “harvesting low-hanging fruits” but now faces a tougher environment shaped by supply-chain disruptions and global competition. “Government has done enough. Now industry has to introspect and identify the gaps,” he said.

One of the biggest gaps is IP. Sanjay Gupta, India Country Head and Chief Development Officer at L&T Semiconductor Technologies, outlined the scale of the challenge. “India does not own a single IP,” he said. Designing one, he noted, will take five to six years. Compounding this is the dominance of Japanese and Western firms in foundational semiconductor technologies and the intense price competition from Chinese fabs, whose costs remain significantly lower.

Despite the IP deficit, some momentum is visible. Sandeep Wadhwa, Executive Director, highlighted the emergence of at least 50 chip design IP entities in India, supported by expensive design tools and specialised training. The government’s ₹76,000 crore National Semiconductor Mission has also placed strong focus on talent development, with 16,000 engineers currently being trained in chip design.

India is beginning to build indigenous processors too, he said, pointing to the development of domestic GPU and CPU efforts, and the interim creation of a processor named OM. “Entire end-to-end ecosystem is being prepared and amalgamating better. This progress is not theoretical,” he said.

The government’s proposed ₹1 lakh crore R&D Innovation (RDI) fund is expected to play a major role in bridging the research gap. Sharma said the sector will urge the government to allocate a portion of this funding specifically for materials research in electronics and semiconductors.

While significant challenges remain—particularly in IP creation, high-end manufacturing, and global competitiveness—the direction of travel is clear. India’s semiconductor sector is no longer content with being an assembly hub. With policy backing, industry collaboration, and a growing talent pipeline, the country is attempting a technologically harder but strategically vital transition.

India’s Semiconductor Mission has now approved a total of 10 fab plants, marking a major step in the country’s pursuit of supply-chain resilience and technological self-reliance.