As West Bengal heads toward Assembly elections, a dramatic confrontation between the Trinamool Congress and the BJP has turned enforcement actions into political weapons, hardening battle lines across the state.

Our Bureau

New Delhi

Kolkata’s winter political temperature has risen sharply, with West Bengal witnessing one of its most acrimonious pre-election confrontations in recent memory. The immediate trigger was the Enforcement Directorate’s search operations linked to the coal smuggling case at premises associated with political consultancy firm I-PAC. But the fallout has gone far beyond the legal action itself, morphing into a full-blown political slugfest that now frames the narrative of the 2026 Assembly elections.

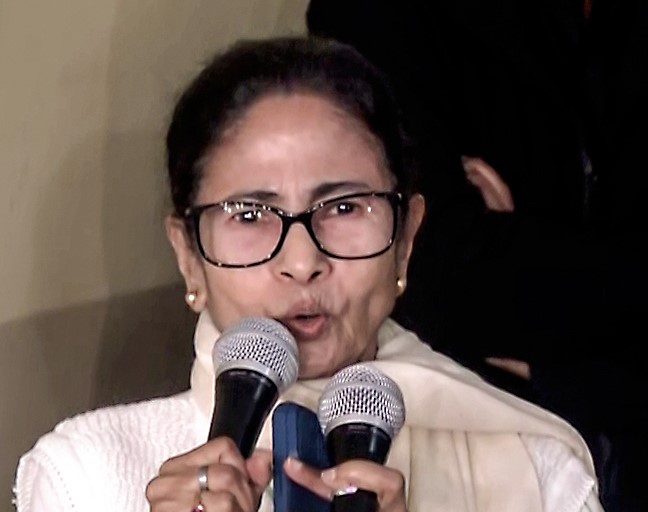

Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee’s dramatic arrival at I-PAC’s office during the ED searches injected high voltage into an already tense atmosphere. Accusing the agency of overreach, Banerjee alleged that party-related data, candidate lists, campaign strategies and electronic devices had been seized illegally. In sharp, characteristically combative language, she accused Union Home Minister Amit Shah of misusing central agencies to intimidate the Trinamool Congress (TMC) ahead of the polls, daring him to come to Bengal and “fight democratically”.

For the TMC, the episode fits neatly into a long-standing political argument: that the BJP, unable to defeat Mamata Banerjee electorally, is deploying central agencies as instruments of political pressure. Party leaders described the searches as an attempt at “data chori” after “vote chori” allegedly failed, claiming that the timing—just months before elections—exposed the political intent behind the action. Street protests, sharp slogans and plans for a statewide agitation quickly followed, with Banerjee herself set to lead demonstrations against what she calls an assault on federalism and democracy.

The BJP, however, has seized on the same episode to flip the narrative. Its leaders argue that the sight of a sitting Chief Minister rushing to the site of an ongoing investigation raises troubling questions. The party has alleged that Banerjee’s actions amounted to interference in a lawful probe and an attempt to shield incriminating evidence. BJP MPs have expanded the attack by questioning I-PAC’s political role and finances, dragging its founder Prashant Kishor into the crossfire and alleging irregularities that, they claim, merit scrutiny.

Caught between these rival claims is the Enforcement Directorate itself, which has insisted that the searches were evidence-based, conducted under legal safeguards and unrelated to elections. In unusually strong language, the agency accused the Chief Minister and state police officials of forcibly removing documents and electronic devices, alleging obstruction of proceedings under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act. The ED’s decision to move the Calcutta High Court has ensured that the political battle will now play out alongside a legal one, with constitutional questions looming large.

Adding another layer to the confrontation, Governor C V Ananda Bose publicly described violence and corruption as “cancerous growths” on Bengal’s body politic. Without naming the Chief Minister directly, he underlined that preventing a public servant from discharging official duties is a serious offence, and that constitutional functionaries are expected to uphold, not obstruct, the law. His remarks have further sharpened tensions between Raj Bhavan and the elected government, a fault line that has been visible for months.

The Congress, struggling to find political space in Bengal’s bipolar contest, has attempted to carve out a middle position. While questioning the timing of the ED raids and alleging misuse of central agencies, state Congress leaders have also asked why the Chief Minister personally intervened during the searches. Their comments underscore a broader reality: the 2026 election is shaping up as a largely binary fight between the TMC and BJP, squeezing smaller parties into the margins.

Beyond the immediate drama lies the deeper political significance of the moment. For Mamata Banerjee, the confrontation reinforces her tried-and-tested campaign frame of “Bengal versus Delhi”, casting herself as the defender of state pride against an intrusive Centre. It is a narrative that has served her well in past elections, particularly among voters wary of central dominance. For the BJP, the episode is an opportunity to foreground corruption, governance failures and law-and-order concerns, while projecting central agencies as acting in the national interest rather than political interest.

Union ministers’ parallel attacks—on healthcare delivery, welfare implementation and alleged infiltration—signal that the BJP intends to broaden the campaign beyond the ED episode. By highlighting the state’s refusal to implement Ayushman Bharat and portraying the TMC government as obstructive and insular, the BJP is attempting to stitch together a development-versus-misgovernance argument to complement its corruption narrative.

As Bengal inches closer to the polls, the I-PAC–ED confrontation may prove to be less an isolated incident and more a defining moment. It has crystallized the core themes of the coming election: federalism versus central authority, corruption versus political vendetta, and strong regional leadership versus national integration. With court battles, street protests and rhetorical warfare all unfolding simultaneously, West Bengal’s election season has begun not with policy debates, but with a bruising contest over power, legitimacy and the very rules of political engagement.