Q&A with Sarah Louise Gates

Sarah Louise Gates is an Australian Cultural Studies PhD Candidate, Kashmir Shaivite Hindu and yoga instructor, finalizing her “thesis of interconnectedness” in yoga and eco-social justice. In an interview with The Indian EYE newsweekly, she spoke about her interest in Indian culture, especially Kashmir Shaivism. Excerpts:

How and why did you become interested in Indian culture and tradition?

My interest in Indian culture and tradition began as a child. There is no answer to the how or the why, it was how life happened. My family were into natural health, lifestyle and spirituality. Meditation, in a traditional yogic method was something I already knew from four. My grandfather and father raised me. We were all vegetarian. Dad was a mental health nurse who meditated and gave energy healing. His spiritual beliefs were very much Hindu. Before he died, we talked about Kashmir Shaivism. We had got to the same end point from two different paths.

A rebellious teen, I left home at 15, moved to the forest and met a pair of Swamis, one of whom, Swami Alokananda Saraswati became my Guru at 16, in 1994. She is an Anglo Indian from Kolkata and would tell me stories of India and Kali which got me inspired. There I learnt integral yoga in the Bihar method as well as my Guru’s refinements from sadhana of kriya yoga. I left that ashram around 2009 feeling that part of my journey was complete.

In 2004 and 2008 I trained to instruct yoga, taught small sessions privately and in the community. Many experiences were unexplained still and I took up jnana yoga. First it was Advaita Vedanta at Swami Venkatesananda’s ashram in Fremantle and in India. From 2014 I came to Kashmir Shaivism with more questions about consciousness, the self and ultimate reality.

Why did you pick the Kashmiri Shaivite tradition as your area of interest and study?

My honours was on “interconnectedness” in ecocritical theory. This was an ambiguous catch word that sounded a lot like a yogic state to me. Nothing really dealt with yogic philosophy in ecocritical theory. It only drew superficially from ‘eastern’ and ‘indigenous thought’. Noticing a gap, I continued with a PhD project on Realising Interconnectedness: A Yogic Ecology. I needed a darshana that recognised the world as both real and sacred. In 2014, I read “The Doctrine of Vibration” by Dr Mark Dyczkowski which set me on the path of Kashmir Shaivism. He was running a course a few months later in Melbourne so I flew over and have since taken Swami Lakshmanjoo as my Sat Guru.

You are working on a thesis of “interconnectedness” of yoga and eco-social justice. Could you please elaborate on it a bit?

The precepts, philosophy and practice of yoga instil values that are essential to overcome many ecological and social issues. Eco philosophers say this is due to a disconnection from nature and one another as human beings. Misunderstanding about who we are and our dharma, or duties at individual, social and universal levels carry society away from right living. Worldly people need to find balance within and without to navigate rapidly changing environmental, social and geopolitical systems.

Decision makers talk about diversity amid unity but competing identities are at odds on who is either accountable or worst impacted by today’s cascading social and environmental crises. Complex thinking requires training and studying Kashmir Shaivism or any dharmic philosophy is a good way to develop viveka and integral thought. Identity cannot be the only platform on which justice is fought, we also need core values for humanity.

Kashmir Shaivism is a householder system that enables ordinary experience to elevate us to self-realisation. In realising our nature, we realise our interconnectedness with all beings and find our hearts are lit by the same universal being. Empathic resonance in a communicative universe, as described in Kashmir Shaivism, one that is imbued with consciousness and creative intelligence, can transform us as individuals to see the world anew. I do not believe we can decolonise anything at all from a colonised mentality and certainly yoga, especially Kashmir Shaivism, are tools to do it.

You must have travelled to Kashmir for your studies. Could you please share some of your experiences?

Kashmir is not considered a safe location for research students. I travelled to Ishwar Ashram in Delhi to study the Paramarthasara and went to Kashi to learn with Mark Dyczkowski. This shaped my understanding of Shiva as I got to spend time in Kaal Bhairav temple which made a big impact on me. He is known as the Chief of Police. He takes care of his devotees, protects them and makes us fearless in the face of death. This connection and devotion to Shiva has helped clear many injustices I faced and to overcome personal losses. I see Shaivism working in reality, uplifting myself and others, giving strength, especially during Covid. Being near the Ganga contextualised a Hindu approach to ‘earth laws’ and how the rivers are understood as the very form of the Goddess, thus with personhood and rights, not just as abstract legal concepts.

Could you please explain what makes the Kashmiri Pandit culture so unique?

Kashmiri Hinduism perceives the entire universe as the divine form. The land, rivers, mountains, springs, all the elements and creatures, every tiny part of Kashmir is the embodiment of divinity. Due to the syncretic nature of Kashmir Hinduism, which blends many philosophical systems, repatriating Kashmir Hindus in exile has never been just about restoring rights to generic ‘Hindus’. In Kashmir Shaivism we see elements of what makes up Kashmir Hinduism: Vedic, Vedantic, Buddhist, Pasupata, Vaisnava, Shaiva, Shakta, Hatha, Ashtanga, Samkhya, classical literary works, dramatology and other influences aside from the Tantric Shaivism for which it is named. Further to this, Kashmir Shaivism is said to have been diffused into the mystical teachings of Sufism, which is also being dominated by fundamentalists in Kashmir.

Every part is like a fractal of the whole. It is this aspect that most impressed me as a student and wanting to understand that I read part of Abhinavagupta’s (10th C) Tantraloka to try to imagine how he thought about Kashmir. There I found that he saw the world in the same unique way Kashmir is represented by other observers. The way in which the textual materials are learnt, brought into comparative synthesis and reorganised into a new system, called Anuttara Trika, is consistent to the integral monist paradigm epistemologically, methodologically and ontologically. Anuttara Trika is unique to Kashmir and quintessentially Kashmiri in character.

Do you think this tradition is under threat? Why?

Kashmir Shaivism is part of Kashmir Hinduism and it sits within that system, informed by it and informing it, as a householder tradition. It cannot be uplifted from Kashmir without changing its form. To reinvent a tradition in a new place requires it to be learnt correctly to begin with which can take many years. There are very few who can do it without destroying it in some way. Lakshmanjoo Academy and Ishwar Ashram Trust were set up to continue the legacy of Swami Lakshmanjoo and Kashmir Shaivism, although it isn’t the same as Swamiji is unparalleled.

I remember one friend in London saying, “How will we go to the river?” Something simple like this may have to be done by a specific river, in a particular place and time with particular people and materials that are only locally available. Combined with displacement the task of passing on the culture, often apart from extended families, is a heavy burden on nuclear families. It takes a village to raise a child and when that village are dispersed all over the world, innovative measures will be needed.

Working alongside and seeing the activities of the Pandit community online proved the benefits of digital technology for awareness raising, political organising, spreading knowledge, sharing traditions and upholding customs including language. There is progress like websites, apps and courses. We are sure to see more. No matter how much is done the race toward westernised “civilisation” takes along in its rapids the interests of young people. Forces behind cultural erasure are not only those we are alert to and have in the past taken both hostile and benevolent appearances.

Indigenocide, like with Tibetan Buddhists or indigenous Australians, once peoples are removed as caretakers of their ancestral lands, their sacred sites and artefacts desecrated or made inaccessible, part of the identity of the people and the consciousness of the community is denied. Kashmir Pandits have had to forge a political identity to defend their rights. Barriers to being heard are media stereotypes that reverse perpetrators and victims and lump this tiny minority from a majority Muslim demographic in with the majority Hindu demographic of India. There are not only Kashmir Pandits affected by the radicalisation and monopolisation of Kashmir’s religious demography. It harms everyone except those who consider martyrdom worth living for.

In academic work on Kashmir Shaivism the cultural custodians are almost never mentioned or depicted with similarly ‘oppressive’ and ‘casteist’ stereotypes despite there being no stratified caste structure among Kashmir Pandits. Their culture has been defined as “Aryan” meaning “invaders” from thousands of years ago, not indigenous and therefore without any special ancestral claims. The same is not said of Kashmiri Muslims despite being of the same stock.

As an international community we have an obligation to do a lot more than just shout slogans about Kashmir Pandit genocide. Media reports that mistake terrorism for activism should be roundly condemned as apologism. Researchers owe duty of care to the vulnerability of this unique community before rewriting their history or misappropriating their intellectual and cultural heritage. Like any other self-determining peoples, the path forward must be indigenous led and administrated and incorporate political and practical solutions to the genocide of Hindus including legal recognition of this crime against humanity still being ignored after 30 years in exile.

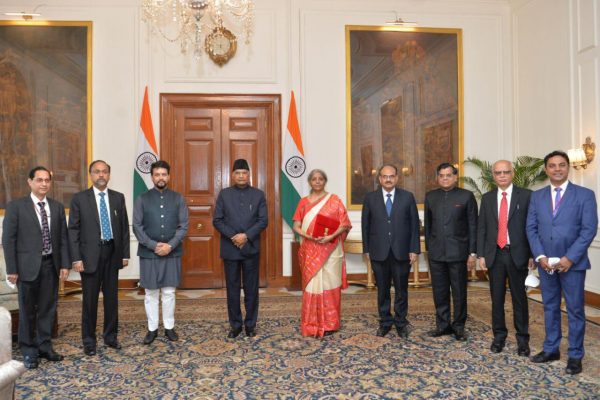

A well written article which brings into focus many questions about livingness. It motivates to go deeper into the areas of basics. My complements for the nice piece. It is more important to me because the pecture includes my mother, third from the left , sitting in the chair. I will send it for publication under your name