The pandemic presents new opportunities for India to rethink its industrial strategy, especially policies concerning the growth of its manufacturing sector

Kogila Balakrishnan

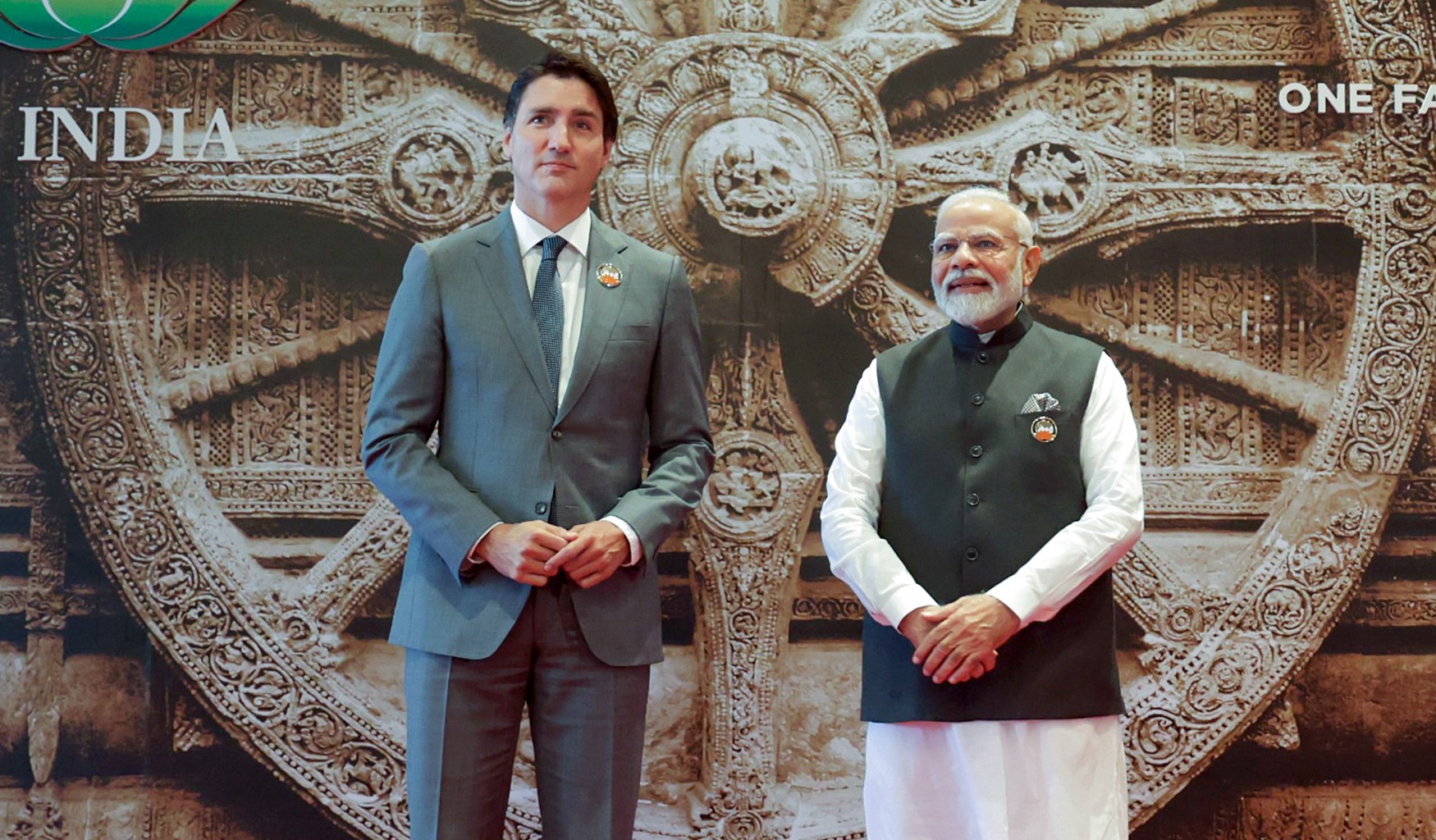

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the inherent weaknesses in the existing global supply chain and the over-reliance on China’s manufacturing industry. Countries such as Japan and the United States (US) have announced their decision to “on-shore”, or pivot, their supply chain out of China. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has called on the Indians to seize the chance presented by the disruption to global supply lines. The Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan (Self-Reliant India Movement) launched by Prime Minister Modi in May 2020 is aimed at merging the global with the local, generating manufacturing investment, and becoming the new global nerve centre of multinational supply chains in the post-COVID world.

However, despite long-term aspirations to become a high-value manufacturing hub, India remains lagging in this area. The pandemic presents new opportunities for India to rethink its national industrial strategy, especially policies concerning the growth of its manufacturing sector. This leads to the question: can India position itself to take advantage of the opportunity that avails to be the next global manufacturing hub?

According to the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO), in 2019, India ranked 42 out of 152 countries, with manufacturing value added (MVA constant 2015 US$) totalling $430.25 billion, or equal to 15.5 per cent of its gross domestic product (GDP). At the same time, China ranked second with MVA (constant 2015 US$) of $4105.87 billion or equal to 28.8 per cent share.

However, India’s policy on foreign direct investment (FDI) and ease of doing business has improved tremendously since 2015. According to the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Ranking 2020, India jumped 79 positions from 142 in 2014 to 63 in 2019. At the same time, China had climbed up from position 90 in 2014 to 31 in 2019.9 India would have to capture a place among the top 50 in the ranking to become a global player in manufacturing.

India’s Manufacturing Lag

There are several reasons why India lags in the manufacturing sector. China has outperformed India, especially in areas critical to boosting manufacturing output such as starting new businesses, access to electricity, registering property, and performance in enforcing contracts.

Pre-COVID, in 2019, China’s FDI inflow stood at US$ 140 billion, whereas that of India’s stood at $49 billion. India liberalised its economy just over a decade after China in 1991, but the move was more cautious than that of China’s, accompanied by sectoral caps. It was only in June 2017 that India abolished the Foreign Investment Promotion Board (FIPB), an inter-ministerial board that granted prior governmental approval in mandatory sectors.

India is also dependent on China for specific critical components. The cell phone industry, for instance, imports approximately 75 per cent of its components from China, with only 12 per cent being manufactured domestically. The chemical used to make cathodes and battery cells for electric vehicles, printed circuit boards, camera modules, and semiconductors are all imported from China.

India’s Manufacturing Policy Initiatives

The Indian Government is committed to improving the ease of doing business and luring FDI into the country. In fact, since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has announced several measures and offered various incentives to attract global investment. According to the latest UN report on world investment, the FDI inflow in China, despite being the second largest recipient of FDI after the US, saw only a marginal increase of 2.1 per cent in 2019. On the other hand, the FDI inflow in India rose by almost 20 per cent in 2019. The COVID-19 supply chain disruptions and lessons learnt may further work to the advantage of India in terms of making it an alternative FDI destination.

In September 2014, Prime Minister Modi launched the “Make in India” initiative to renew focus on 25 key sectors ranging from automobiles to information technology and business process management (BPM). The initiative is built on four pillars: policy initiatives and new processes, robust infrastructure, focus sectors, and a new mindset approach. In May 2017, the Ministry of Defence’s Defence Acquisition Council approved the “Strategic Partnership” model which enables private companies to tie up with foreign players in manufacturing high-tech defence equipment such as submarines, fighter jets, helicopters, and armoured vehicles in India.

The series of policy reforms and notable improvements in the business regulatory framework has had a tremendous impact on the development of India’s ability to attract FDI and trade in the manufacturing sector. In fact, the World Bank’s Doing Business 2020 report ranked India as one of the 10 most improved economies in terms of ease of doing business score, especially due to reforms in paying taxes, trading across borders, and resolving insolvency.

Other positive developments included improvement in India’s ranking in award of Construction Permits, from 184 in 2014 to 27 in 2019; and in Getting Electricity, from 137 in 2014 to 22 in 2019. Among 190 economies, India now ranks 13 in Protecting Minority Investors and 25 in Getting Credit.

Conclusion

India has a huge young demographic, between 40-60 per cent of the country’s population, which requires jobs. India would have to commit to more policy reforms to be able to further scale up its manufacturing capacity. It must continue to significantly invest in the development of physical infrastructure and digital connectivity—high-speed train networks, new airports, seaports, roads, and broadband. It is important to offer efficient connectivity between industrial clusters and cities ensuring good transport links and logistics that support an effective and reliable industrial eco-system, which meets the demand of the international supply chain.

India also needs to liberalise its education sector and invest in international education and research partnerships. These efforts should be fortified by a government-led public-private partnership investments in R&D, innovation, entrepreneurship, and the strengthening of the industrial supply-chain in high-value manufacturing sectors, which will contribute to the development of regional clusters. One such initiative is the C-130J programme that created a partnership between the Lockheed Martin research programme and Indian universities to work with local industries and mentors from the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) to help design specifications.

To support industrial clusters, India must consider prioritising investment into alternative renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power. Currently, India is struggling to provide cheap access to electricity and clean water. Cheap renewable energy can generate capability and reach remote rural areas across the country; the surplus can be used for electric vehicles, such as scooters and rickshaws, which can then be locally produced for domestic and export markets. At the same time, these green technology related energy management initiatives will also address externalities such as high levels of carbon emission, pollution, and poor air quality and contribute towards sustainable manufacturing.

Additionally, there is a need to improve and follow-through India’s regulatory reforms such as labour and land acquisition reform, commercial law approval processes and regulations, tax credits and grants for investors in the emerging high-value manufacturing technology as well as enforcement of contracts. India can also introduce incentives to encourage advanced technology innovations in areas such as 3D printing and automotive real-time processes in manufacturing.

Last, but not least, the Indian small and medium enterprises (SMEs) sector should be incentivised to become internationally competitive and export-driven. Both state governments and the central government must coordinate and introduce incentives that will draw FDI at regional levels, as has been seen in Telangana and Tamil Nadu. The government needs to further reduce red tape and overly complex approval processes and promote innovative and efficient business processes that will attract more foreign investors.

India can emerge as the next global manufacturing hub. In times of deep economic crisis, such as the one brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, a swift government intervention through strong fiscal response and injection of capital into the economy is necessary. While the economy as a whole needs significant support, the government must see this as an opportunity to strategically invest in high technologies for priority sectors such as agriculture, electronics and electrical equipment, including computers, telecommunication and space. It should inject aggressive economic incentives and review the current business practises to bring in more trade and investments into advanced manufacturing sectors.

At the same time, the commercial sector, especially electronics and electrical sectors, must be incentivised to attract FDI from global electronic component manufacturers, review existing business models, and invest in upskilling and retraining as a move to enhance overall industrial capability and capacity. India should now turn to greater public-private partnership collaborative model, where the government and industry take collective responsibility for promotion and growth of the Indian manufacturing sector. Finally, India should capitalise on its diaspora and international industrial partnership programmes, such as the Access India Programme (AIP) introduced under the United Kingdom India Business Council (UKBIC), to generate new opportunities for innovation and entrepreneurship.

Dr. Kogila Balakrishnan is Director, Client and Business Development (East Asia) at WMG, University of Warwick; Adjunct Professor at Malaysian National Defence University; and former Under Secretary, Malaysian Ministry of Defence

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

This is the abridged version of the article which appeared first in the Comment section of the website (www.idsa.in) of Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses, New Delhi on November 17, 2020