As the US carries out its tariff war and struggles with strained alliances, India, Russia, and China are strengthening ties under platforms like the SCO and BRICS, redefining the balance of global power

Our Bureau

Tianjin/ New Delhi / Tokyo

For much of the post-Cold War era, the global system has been described as unipolar, dominated by the economic, military, and technological clout of the United States. That order is now showing unmistakable signs of strain. Leaders across Eurasia—from Moscow to Beijing to New Delhi—are calling for an end to unipolarity and working to shape a more balanced, multipolar system.

Russian President Vladimir Putin articulated this vision most directly during his recent visit to China, where he described the very notion of a unipolar world as “unfair” and unsustainable. He stressed that a multipolar system does not mean a new hegemon taking the place of the US, but rather a framework where “all actors of international relations must be equal.”

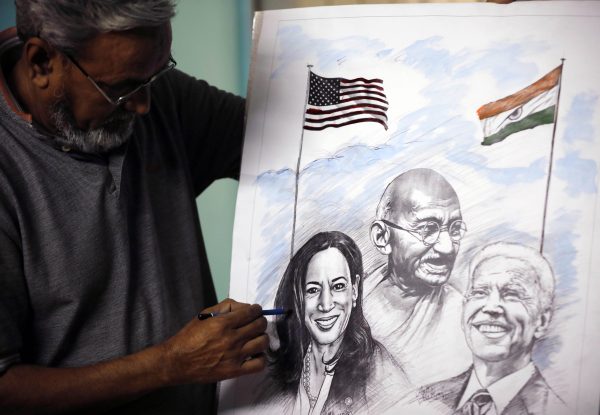

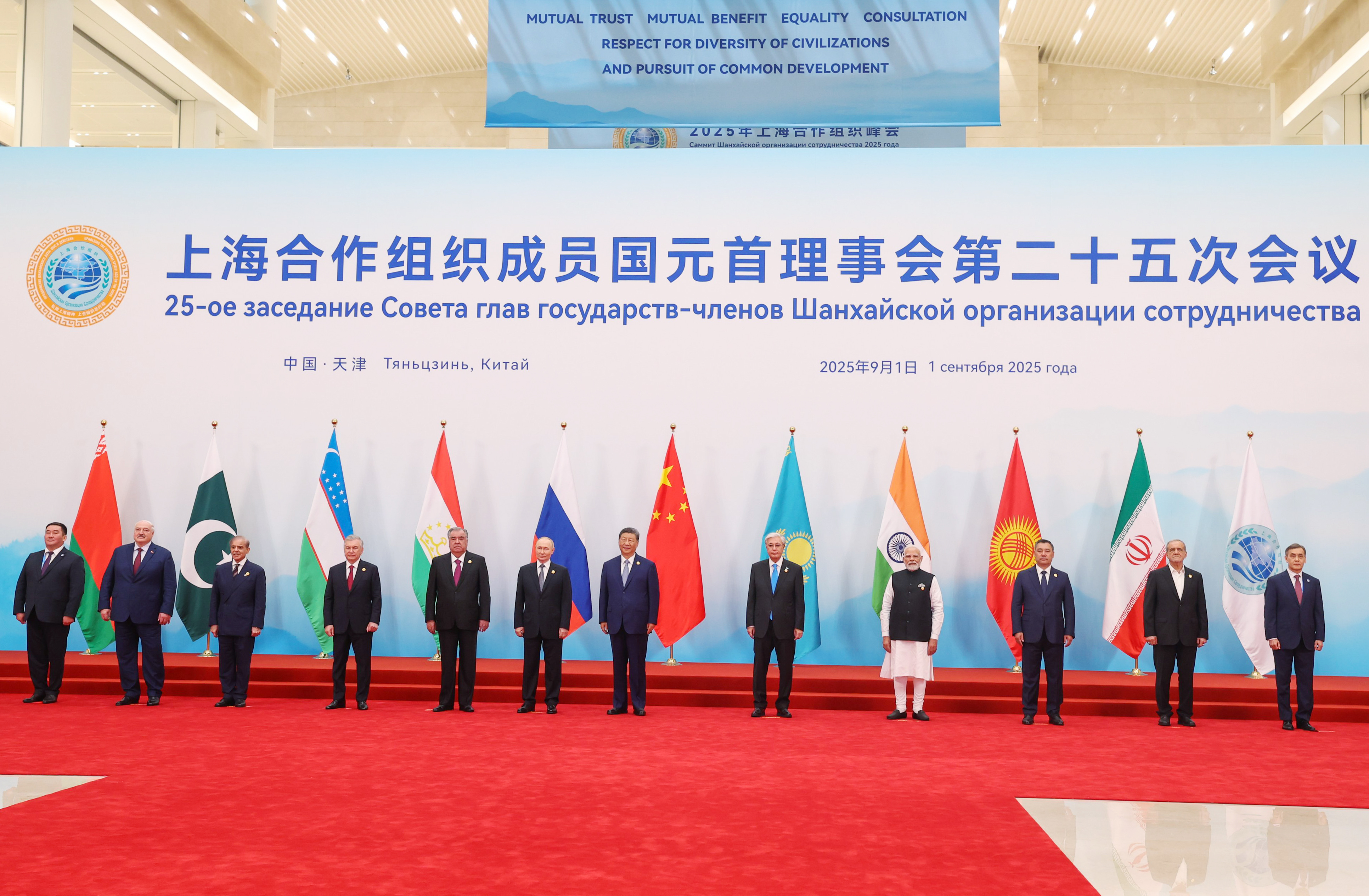

This thinking is increasingly echoed in forums such as BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). These platforms not only give voice to the collective concerns of the Global South but also provide tangible mechanisms to reshape trade, security, and technological cooperation. The SCO Summit in Tianjin underscored this momentum, with leaders discussing reform of global governance, counter-terrorism strategies, and cooperation in cutting-edge areas like artificial intelligence.

The outlines of multipolarity are visible: large economies like India and China, energy powerhouses like Russia, and a coalition of middle powers from Central and Southeast Asia are coordinating more actively than at any point in recent decades. While disagreements among them remain, the very act of consensus-building reflects a slow but steady shift away from Western dominance.

India at the Center

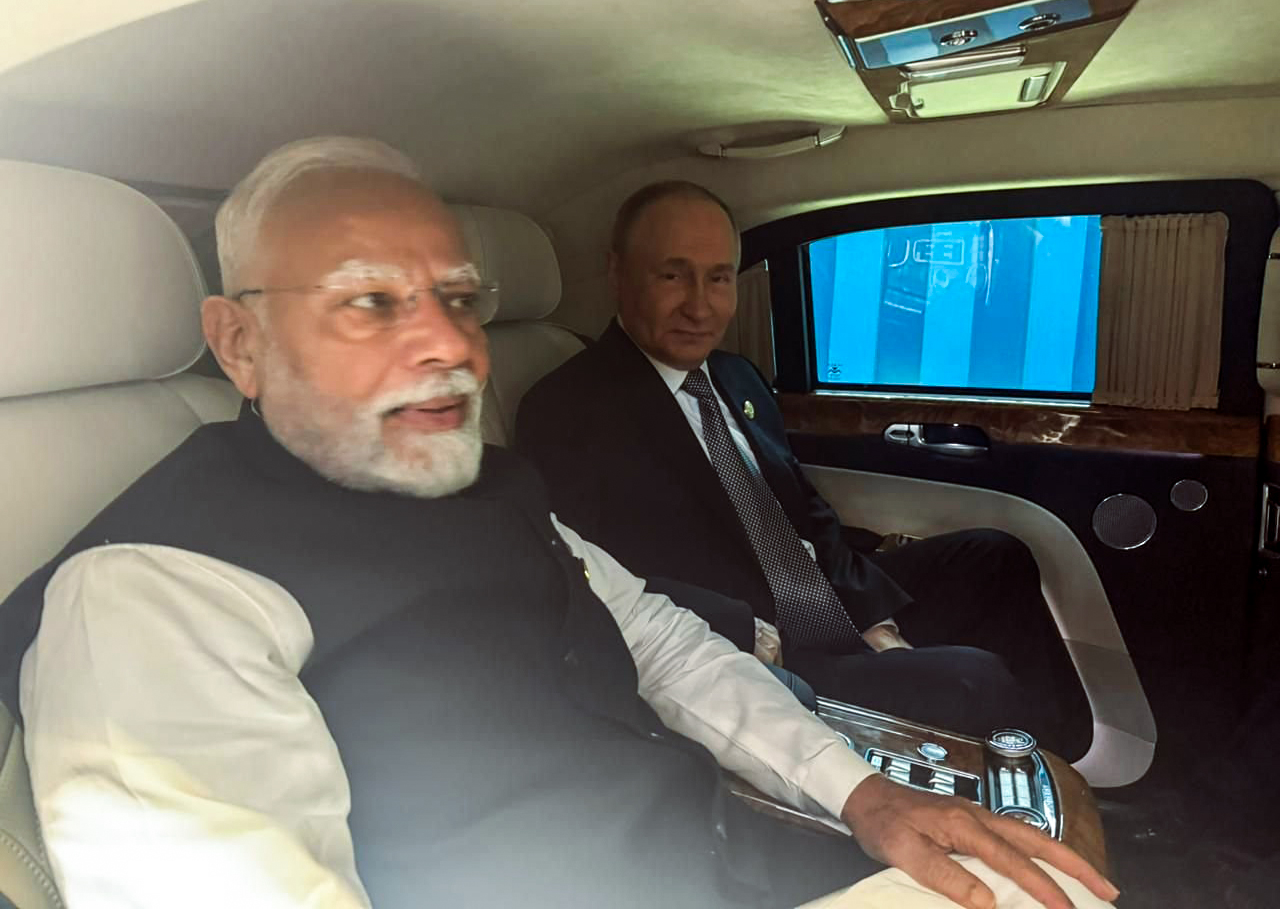

Amid this transition, India’s role is proving decisive. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s back-to-back visits to Japan and China in late August highlighted how New Delhi is positioning itself as both a bridge and a balancing power. At the 25th SCO Summit, Modi met with President Putin and President Xi Jinping, affirming India’s willingness to shape the rules of engagement in Asia and beyond.

In his speech at the SCO, Modi underlined three pillars for cooperation: security, connectivity, and opportunity. His emphasis on countering terrorism resonated strongly after the Pahalgam attack, and the summit’s final declaration reflected India’s concerns by condemning cross-border terrorism. That alignment suggested a greater receptiveness from China, which has often been accused of shielding Pakistan at international forums.

Equally significant was Modi’s bilateral meeting with Xi Jinping. Both leaders spoke of India and China as “development partners, not rivals,” signaling a willingness to stabilize relations that have been strained since the 2020 border clashes. Although differences remain profound, the recognition that disputes should not define ties points to a pragmatic recalibration.

India’s diplomacy with Russia, meanwhile, remains one of its strongest assets. In Tianjin, Modi and Putin reaffirmed the “Special and Privileged Strategic Partnership,” marking its 15th anniversary this year. From energy supplies to defense cooperation, India-Russia ties remain resilient even under Western sanctions pressure. Modi’s assertion that India and Russia have always stood “shoulder to shoulder” carried both symbolic and practical weight.

By deepening partnerships across Asia while maintaining strong relations with Japan and engaging the West selectively, India is carving out space as a central player in shaping multipolarity. Its message is clear: New Delhi seeks not isolation from the West, but an end to dependency on it.

From Dominance to Dilemmas

The rise of this multipolar world poses the most direct challenges to the United States. For decades, Washington invested in drawing India closer, particularly after the Cold War, with the twin goals of countering China and gradually reducing India’s reliance on Russia. Yet recent US policies under President Donald Trump appear to have undercut that long-term strategy.

The imposition of steep tariffs on Indian goods—50 percent across the board, with an additional 25 percent penalty linked to India’s purchase of Russian crude—has strained the relationship significantly. Former US National Security Advisor John Bolton lambasted the policy, accusing Trump of “shredding decades of Western efforts” to align India away from Moscow and toward Washington.

For American allies in Europe, the SCO summit was a sobering reminder of shifting power dynamics. Finnish President Alexander Stubb openly warned that if the West fails to adopt a more cooperative and respectful foreign policy toward the Global South, it risks losing global influence. The criticism was not only aimed at the tariff war but also at the broader inability of the US to recognize the agency of emerging powers.

Within the US itself, Trump’s approach has drawn domestic criticism, with analysts warning that his tariff strategy is isolating Washington at a moment when it needs allies most. Bolton noted that the tariff war had effectively “pushed Modi closer to Russia and China,” handing Beijing an opportunity to present itself as a credible alternative.

The longer-term risk for Washington is not merely economic. Platforms like the SCO are now openly considering alternatives to the IMF and World Bank, including a new development banking system that could rival the Bretton Woods institutions long dominated by the West. If realized, such initiatives could diminish American financial leverage, a cornerstone of its global influence.

An Uncertain Future

The evolution toward multipolarity is not without its challenges. Differences among the key players—India, Russia, and China—are substantial. Border disputes, competition for regional leadership, and diverging economic interests mean that unity is far from guaranteed. Yet the willingness of these powers to set aside disputes, at least temporarily, to articulate a shared vision of global governance represents a historic departure from past patterns.

For India, the balancing act remains delicate. While it strengthens ties with Moscow and Beijing, New Delhi is equally keen to maintain its growing partnerships with Washington, Tokyo, and European capitals. Modi’s recent Tokyo visit reaffirmed the vitality of India-Japan cooperation, particularly in technology and infrastructure. This multi-directional diplomacy suggests that India is less interested in choosing sides than in shaping the architecture itself.

For Russia and China, India’s involvement provides credibility and breadth. Unlike Moscow or Beijing, New Delhi does not carry the baggage of direct confrontation with the West, allowing it to engage more flexibly across multiple arenas. This makes India indispensable to any multipolar arrangement.

The US, however, faces a narrowing window of opportunity. Analysts like Waiel Awwad have observed that Washington perceives forums like the SCO as explicitly counter-hegemonic. If the US continues with unilateral tariffs and coercive measures, it risks further alienating partners and accelerating the very multipolarity it resists.

The West can still adapt. By adopting what Finnish President Stubb called a “dignified and cooperative” foreign policy, the US and Europe could work with, rather than against, the Global South’s aspirations. Acknowledging India’s leadership role in Eurasia and the broader South would be a critical first step.

The Tianjin SCO Summit was more than a diplomatic event—it was a symbolic marker of the shifting tides in world politics. As leaders from India, Russia, and China converged, they collectively sent a signal: the age of unipolarity is waning, and a new, more plural order is in the making.

India’s diplomacy has positioned it at the heart of this transition, enabling it to influence not only Asia’s trajectory but also the contours of global governance. For the US, the path ahead is fraught: resist multipolarity and risk isolation, or adapt and engage with a world no longer defined by a single center of power.

The emerging order is unlikely to be smooth, and contradictions will abound. Yet the direction of travel is clear. The world is entering a new phase—one where India, alongside Russia and China, is helping redraw the map of power for the 21st century.