Manoranjan Srivastava

India is one of the world’s fastest growing major economies with a population of around 1.4 billion, and is likely to become world’s third largest economy in 2027. The economic and social development of its large populace is intrinsically linked with its energy requirements and consumption. The energy needs of India are therefore bound to grow in future and its energy security is going to be of strategic importance.

Even as India is poised to be a crucial player in the global energy market, its accomplishment in energy development has been extraordinary. From being a power deficient nation with profound leaning on coal for its energy requirements, its journey to a power surplus nation is incredible. Presently, its total installed electricity capacity stands slightly more than four lakh MW. India is the third largest renewable energy producer in the world and non-fossil fuel sources contribute 40 per cent of its installed electricity capacity.

India ranks fourth globally in energy consumption behind China, the US and the European Union (EU). As per the International Energy Agency (IEA), India is likely to overtake the EU by 2030 and to move up to the third spot. Per capita energy consumption in 2021–22 in India was however awfully low at 1255kWh, almost one-third of the global average. The IEA has forecasted that in the coming two decades, India would account for the largest energy demand growth.

From depending heavily on fossil fuel, India has rapidly shifted towards clean and renewable sources of energy. It has provided electricity connection to millions and promoted schemes like Unnat Jyoti by Affordable LEDs for All (UJALA) and Street Lighting National Programme (SLNP) enhancing energy efficiencies. Concerns for climate change and sustainable development goals (SDGs) have pushed India to expand its renewable sources of energy. Setting an eye on becoming the world’s largest green hydrogen hub, India in January 2022 approved the National Hydrogen Mission to reduce dependency on fossil fuels. The present decade has also witnessed unprecedented reforms, technological advancements, policy decisions and collaborations in the turf of solar and wind energy, both of which have the potential to surge ahead of coal and gas.

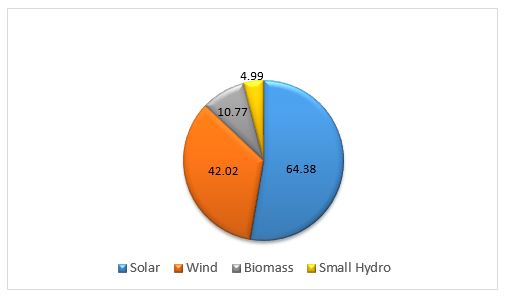

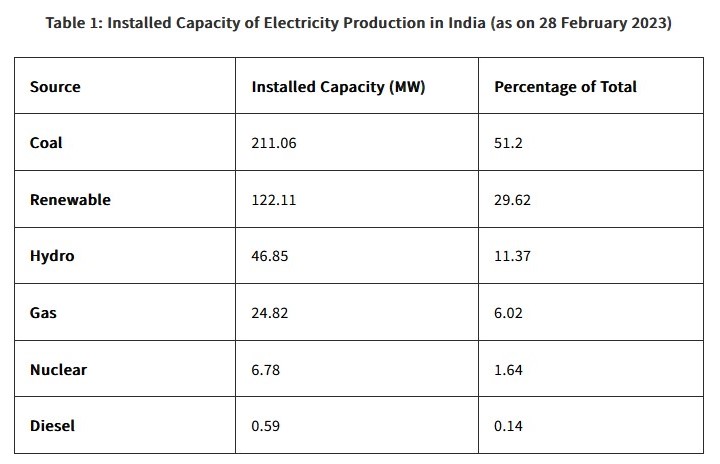

Table 1 shows the installed capacity of electricity production in India, as on 28 February 2023. The contribution of renewables is nearly 41 per cent with production of around 169 GW (including large hydro). Pie Diagram 1 illustrates that the wind and solar have lion’s share of around 87 per cent of the total renewable energy installed capacity.

The story of renewable energy in India dates back to 1960s when windmills were developed by the National Aeronautical Laboratory (NAL). In 1982, the Department of Non-conventional Energy Sources (DNES) was established under the Ministry of Energy. Confronted by oil crisis, India started seeking alternative sources such as renewable energy to achieve energy security, economic development and to mitigate climate change. In 1992, the DNES was rechristened as Ministry of Non-Conventional Energy Sources and was thereafter renamed as the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) in 2006.

With rapid urbanisation, the onshore wind industry is facing problems such as paucity of land resources and exhaustion of best windy sites. On the other hand, the better-quality obstruction free wind availability in open seas has resulted in spotlight turning towards offshore wind energy. India’s large peninsular area with an equally large coastline of 7,516 kms enhances prospects of harnessing offshore wind energy. To tap this vast renewable energy potential, Government of India in 2015 notified the ‘National Offshore Wind Energy Policy’ which designated the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy as the nodal Ministry for development of Offshore Wind Energy in India.

The MNRE has been entrusted with the responsibility of Development and Use of Maritime Space within the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of the country and for overall monitoring of offshore wind energy development in the country. Significant headway has been made since then. The initial assessment undertaken by National Institute of Wind Energy (NIWE) indicates a total wind energy potential of 302 GW at 100 meters hub height. The MNRE has further specified that initial studies indicate an estimated offshore wind energy potential of about 70GW within identified zones of Gujarat and Tamil Nadu.

The story of global offshore wind energy is around three decades old. The first offshore wind turbine was established in 1991 (decommissioned in 2017) in Denmark, as a demonstration project.10 India’s endeavours in this area commenced in 2013 with the project ‘Facilitating Offshore Wind Energy in India (FOWIND)’, which intended to identify potential zones in Gujarat and Tamil Nadu to foster India’s transition towards clean technologies. The project was undertaken with assistance of Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC) and was supported by European Union (EU).

Another project, Offshore Wind Power project in India (FOWPI) supported by EU is underway since 2015 and has provided invaluable assistance in capacity building of Indian stakeholders and for Pre-Financial-Investment-Decision. The data obtained from satellite and other sources has helped in identification of eight potential offshore zones off Gujarat and Tamil Nadu and formulation of the preliminary assessment report. As per the report, prospects exist for exploitation of 36 GW and 35GW of offshore wind energy off Gujarat and Tamil Nadu respectively.

Proactive actions have been taken further and the ministry has initiated steps such as issuance of Strategy Paper for offshore wind development which envisages three models for developing these offshore wind sites. Another significant progress has been commissioning of a Light Detection and Ranging (LiDARs) off Gujarat coast near Pipavav in 2017 for Offshore Wind Resource assessment. The data collected has been analysed to validate the satellite data and published by NIWE.

Given the demand and supply reasons, the REEs of late have been gaining immense strategic value becoming crucial link in the complex global value chain. The Rare Earths crunch in 2010, though short-lived, elicited geopolitical considerations and proposals started floating to look for alternate solutions such as mining in Amazon rainforest or sea bed or even looking at the option of obtaining it from the moon. The US proclamation that mining of REEs is an issue pertaining to national security therefore seems to be unambiguous.

Conservationists have been vociferous in expressing the adverse impact of deep-sea mining on the ocean environment which is already facing threats from global warming, ocean acidification, pollution, plastic debris, and over fishing. The fear of deep-sea mining having cascading effect on ocean stability and ocean food web therefore needs to be factored into prior to undertaking any activity in the last untouched frontier of this planet. The oceans are the largest habitat of life, numerous of them being unknown and yet to be discovered.

The deep seabed minerals exploration and exploitation in ‘the Area’ defined as the seabed and subsoil beyond the national jurisdiction limits, is regulated by the International Seabed Authority (ISA). ISA is an autonomous organisation established by United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) on 16 November 1994. A contract with the ISA is imperative to undertake activities related to exploration and exploitation of seabed mineral in the Area. So far, 29 exploration contracts for an area comprising more than 1.3 million sq km of the ocean floor have been issued in the Indian, Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

India plans to develop reliable deep-sea mining to tap ocean resources to address its need for rare earth minerals from the CIOB which has estimated resource prospects of around 380 million tonnes of polymetallic nodules consisting of 4.7 million tonnes of nickel, 4.29 million tonnes of copper, 0.55 million tonnes of cobalt and 92.59 million tonnes of manganese. The huge mineral resources can help India in becoming self-sufficient in these critical metals and cut the supply chain vulnerabilities.

From the prism of geo-economics, prioritising deep sea mission seems as an inescapable necessity for India. The availability of REEs is crucial for India as it aspires to take centre-stage in manufacturing of strategic defence systems, semiconductors and clean energy systems. Presently, India’s requirement of REEs is met mostly through imports. India therefore must explore options to harness its land-based sources and collaborate with like-minded partner countries to meet the growing demand of critical minerals and REEs.

The Toyota Tsusho Corporation has been undertaking REEs production activities at Visakhapatnam through its subsidiary unit. India has future plans to start REEs mining activities at more sites such as coastal belt in Puri, Odisha and collaboration with Japan would be crucial in such endeavours. Japan also aims to commence extraction of rare earth metals from deep sea in 2024 by developing robotic deep sea mining technology. It has one of the world’s richest seabed minerals deposit in the areas such as Okinawa trough and Minami-Torishima islands. A collaboration between India and Japan to tackle the challenges of deep-sea mining and technology development thus holds immense potential and could prove vital.

The contours of deep-sea mining which pose strong environmental, technological and social challenges also provide India an alternate and a viable solution to meet its quest for these critical minerals. Scientific pursuits, environmental assessments and scaling up of capacity and capabilities must therefore continue as India advances for further exploration of the deep ocean for resources.

Comdt Manoranjan Srivastava is Research Fellow at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

The full version of this article first appeared in the Comments section of the website (www.idsa.in) of Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses, New Delhi on October 4, 2023