R. Vignesh & Abhay Kumar Singh

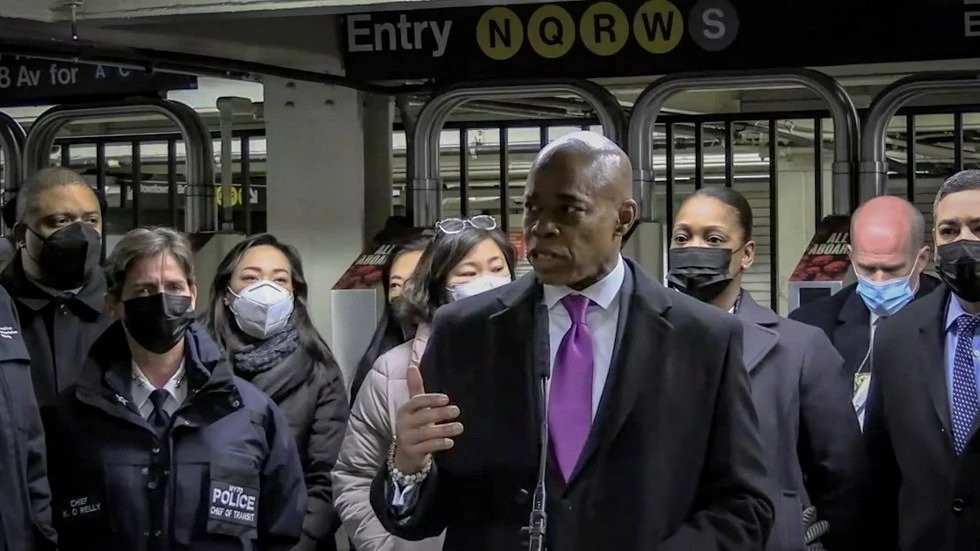

On 13 September 2023, the port city of Sevastopol in Crimea was attacked by Ukrainian missile strikes. As per reports, Ukraine carried out this strike using Storm Shadow cruise missiles that it acquired from the United Kingdom (UK) earlier this year. Ukraine supposedly fired ten of these missiles, of which three managed to penetrate the Russian Air Defence Grids. Two Russian warships that were undergoing repairs in the dry dock sustained severe damage and were rendered inoperable. This included a large surface and submersible vessel that has been identified as a Landing Ship (LST) and a submarine.

The naval base at Sevastopol is the home to the Russian Navy’s Black Sea Fleet and has a storied history. As a warm water port with a natural harbor and extensive infrastructure, Sevastopol is among the best naval bases in the Black Sea region.

Sevastopol also played a critical role in supporting Russia’s four-month long occupation of Snake Island. During the initial weeks of the War, many observers speculated that Sevastopol would be the staging point for potential Russian amphibious operations on Odesa. On a regular basis, Russian surface ships and submarines employed in combat operations berthed in Sevastopol for re-arming, replenishing and repair. The geographic advantages and the infrastructure facilities available in Sevastopol enabled the Black Sea Fleet to make the optimal utilisation of its Operational Turnaround (OTR) and firepower against Ukrainian targets.

Thus far, the attack on 13 September 2023 is the most successful attack considering the damage inflicted upon Russia’s naval assets in Sevastopol. Since then, there have been several independent BDAs released by various Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) platforms. The analysis of these BDAs provides a holistic picture of the nature and extent of loss that the Russian Navy incurred in this attack. Of the three missiles that had penetrated the Russian air defence grid, one had struck the submarine while the other two had hit the LST.

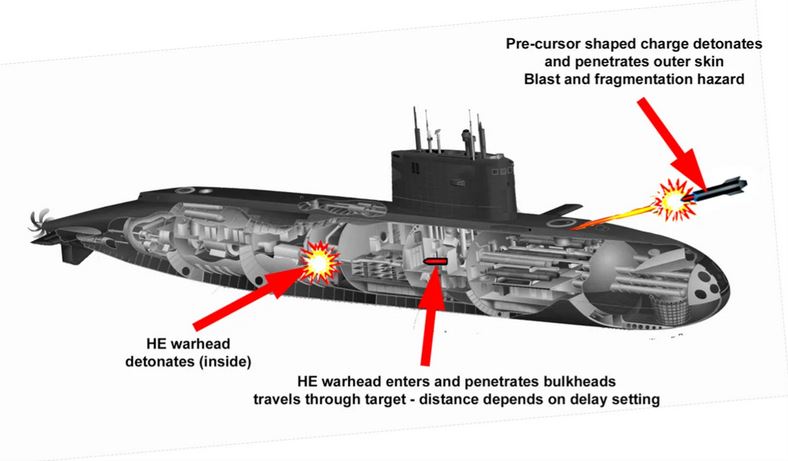

The Submarine has been identified as an improved Kilo-Class submarine called the Rostov-on-Don. This class of vessels are conventional submarines (SSK) with a dual hull design. The inner hull is called the pressure hull, designed to withstand the immense pressure of the deep sea and houses the crew and equipment. While the outer hull is the structural hull designed to protect the inner hull from damage. The photographs of the damaged submarine released by Conflict Intelligence Team (CIT) indicate that the missile had penetrated both the hulls and the warhead has exploded inside the pressure hull. The possible trajectory and the damage inflicted on the submarine has been illustrated in Image 1 released by the Kyiv Post.

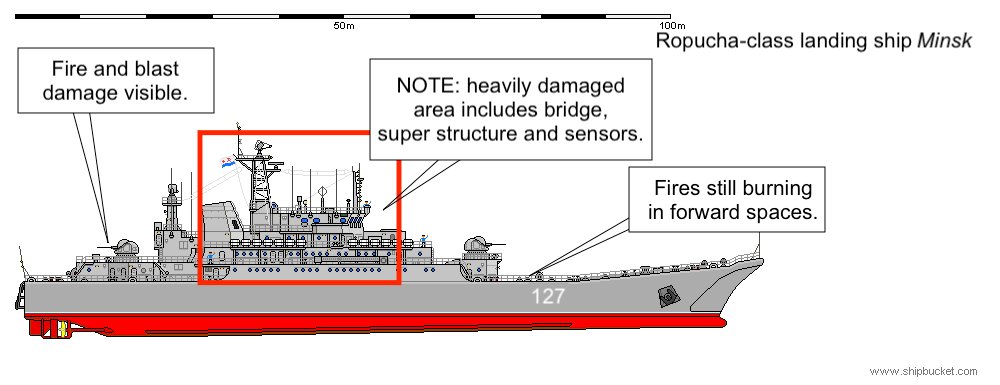

The other significant target of the attack has been identified as a Soviet Era Ropucha-class LST named as Minsk. These class of ships were designed for beach landings and were capable of transporting cargo up to 450 tons. The structure of these ships has been designed to have both bow and stern doors, making it possible to load and unload vehicles easily. The Minsk was among the six LSTs that entered the Black Sea through the Turkish Straits in January 2022. In the initial weeks of the war, it was expected that these ships would serve as the backbone of the much-anticipated Russian amphibious operations on the southern coast of Ukraine.

It is possible that Minsk, like Rostov-on-Don, has been damaged beyond repair. This is contrary to Russia’s claims that these vessels would be swiftly repaired and put back into service at the earliest. Considering the various independent BDAs of the Sevastopol attack, it would be safe to assume that both these significant assets of the Russian Navy are most likely to be written off from service. Image 2 shared on Twitter by conflict correspondent Chuck Pfarrer illustrates the extent of possible damage sustained by Minsk.

The lateral damage of this attack has been on the dry docks where these two vessels have been undergoing repairs. Since the beginning of the war, the Sevastopol Shipyard has been engaged in the repair and re-equipment of the Black Sea fleet’s ships and submarine. Experts have opined that there are no comparable facilities within the Black Sea capable of conducting major repairs works on Russian warships. For example, the nearest Russian port in Novorossiysk which is located about 500 kilometers east of Sevastopol does not have facilities for servicing naval vessels like submarines. Hence the Sevastopol Shipyard is a critical infrastructure facility supporting the Russian War effort in the Black Sea.

Apart from the likely destruction of the vessels and damage to the dry docks, the attack is indicative of some larger trends that are emerging in the maritime theater of the Ukraine War.

In the initial weeks of the War, Ukraine’s maritime strike capability was largely confined to its immediate coastal waters and Russian warships operated with impunity on the high seas. Despite their limited strike capability, the Ukrainian Navy using coastal missile batteries and UAVs was successful in targeting the Russian-occupied Snake Island situated just 19 nautical miles off the coast of Odesa. During this time, the erstwhile flagship of the Black Sea Fleet was reportedly struck and sunk by Ukrainian anti-ship missiles.

The attacks on Sevastopol and the Kerch Bridge that began in October 2022 indicated the expansion of Ukraine’s maritime strike capability to Crimea. Following this, the Black Sea Fleet began relocating some of its ships and submarines from Sevastopol to the Novorossiysk, situated on the Russian Mainland.16 But with the recent attacks, it has become clear that Sevastopol has become even more vulnerable and will most likely force the Russian Navy to relocate the Black Sea Fleet to Novorossiysk. However, on 4 August 2023, the Ukrainian Navy successfully attacked even the Novorossiysk base using USVs and reportedly damaged a Russian Warship. Hence, Ukrainian Maritime Strike Capability has consistently expanded, bringing the war to Russia’s Southern coasts as illustrated in Map 1.

Since the beginning of the War, the airspace over Crimea has been protected by Russian Air Defence grids consisting of an extensive network of S-400 and S-300 missiles. Due to this, Ukraine’s attacks on the Crimean Peninsula were predominantly carried out using UAVs and USVs. The ability of these drones to inflict damage upon Russian military targets in Crimea was also limited. But the attack on 13 September 2023 was carried out using cruise missiles that managed to penetrate Russia’s air defence grid and strike vital targets. Earlier on 23 August 2023, Ukraine had claimed that it had successfully destroyed an S-400 battery in Crimea and released a video of the purported attack.

It must be noted that in the initial months of the war when the strategically located Snake Island was under Russia occupation, Ukraine adopted the tactic of interdicting the Black Sea Fleet’s supply chain. Despite its then limited strike range, Ukraine began targeting Russian supply ships headed to Snake Island using drones and anti-ship missiles. This tactic was successful as it made Russia’s occupation of Snake Island very difficult and subsequently led to their withdrawal on 30 June 2022.

Extensive Ukrainian missile and drone strikes on the Black Sea Fleet’s infrastructure in Crimea have already disrupted Russian Ground Lines of Communication (GLOCs). Recently, it was confirmed through satellite imagery that the 744th Communications Center of the Black Sea Fleet in Crimea had been struck by Ukrainian missile strikes on 20 September 2023. Also, in September, the Ukrainian forces gained control of several offshore oil drilling platforms close to Crimea. Ukraine has claimed that it has captured radar systems from these platforms that can track movements of Russian ships in the Black Sea. Observers have opined that through such attacks, the Ukrainian Military has achieved effects beyond just the degradation of Russian naval capabilities. The imminent threat to the Black Sea Fleet’s supply chains and communication networks from Ukrainian strikes severely undermines Russia’s ability to protect Crimea.

The attack on Sevastopol not only casts an undermining effect on the capabilities of the Black Sea Fleet but also on the morale of Russian military personnel and civilians in Crimea. Sevastopol, being the home of the Black Sea Fleet, used to witness elaborate military parades for Russia’s Navy Day Celebrations held every July. On the other hand, since the Soviet Times, Crimea has been a popular summer destination for Russian tourists. After Crimea came under Russian control in 2014, inflow of tourism exponentially increased from 5 million in 2015 to 9.4 million by 2021. The local economy of Crimea is heavily reliant on tourism and Russia has heavily invested in infrastructure facilities for tourists.

Overall, these developments indicate that the battle lines in the maritime theatre of the Ukraine war have undergone major changes. In the coming days and months, Ukraine could further attempt to scale up its attack on Crimea. This would make Sevastopol an unsafe naval base for the Black Sea Fleet. In such a scenario, there is a possibility that the Black Sea Fleet will be completely relocated to Novorossiysk. Due to this, the OTR and supply chains of Russian warships and submarines will become overstretched. This would make the Black Sea Fleet less efficient and more vulnerable in its naval operations against Ukraine. Due to this, Russia’s ability to dominate the north-western part of the Black Sea will be considerably diminished. This will result in Ukraine having more secure access to its coasts and its military will be in a better position to challenge Russia’s dominance of the Black Sea.

Dr R. Vignesh is Research Analyst at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (MP-IDSA), New Delhi

Cmde Abhay Kumar Singh (Retd) is Research Fellow at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

The full version of this article first appeared in the Comments section of the website (www.idsa.in) of Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses, New Delhi on October 4, 2023